By CoCash

The World of Polyhedra: Shapes That Build Space

Polyhedra are among the most striking creations in the landscape of mathematics. These three-dimensional solids, constructed from flat polygonal faces, straight edges, and sharp vertices, form the foundation of geometric reasoning, architectural design, crystallography, and even modern computer graphics. Though they may appear simple at first glance, polyhedra hide deep mathematical structure, symmetries, and connections that stretch across centuries of human thought.

What Defines a Polyhedron?

A polyhedron is a solid made from flat faces that are polygons. Each polygon meets others along edges, and the edges meet at points called vertices. A shape becomes a polyhedron when it satisfies three conditions:

Flat faces (no curves) Straight edges Enclosed volume

This deceptively simple definition creates an entire universe of forms.

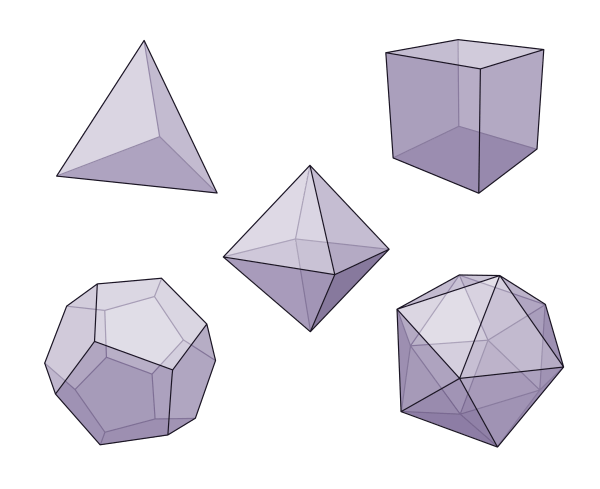

The Classical Giants: Platonic Solids

Five polyhedra stand apart as the most symmetrical and historically significant. Known since antiquity, the Platonic solids have identical faces, edges, and angles:

Tetrahedron – 4 triangular faces Cube (Hexahedron) – 6 square faces Octahedron – 8 triangular faces Dodecahedron – 12 pentagonal faces Icosahedron – 20 triangular faces

They appear in philosophy, natural patterns, crystal structures, and even the design of gaming dice.

Beyond Perfection: Archimedean Solids

While Platonic solids use only one type of face, the Archimedean solids mix different polygons while still maintaining symmetry. Examples include:

Truncated tetrahedron Truncated cube Cuboctahedron Icosidodecahedron Snub cube Truncated icosahedron (the familiar “soccer ball” pattern)

These shapes often emerge in chemistry, architecture, and molecular models.

Prisms, Antiprisms, and Johnson Solids

Outside the high-symmetry families, polyhedra expand dramatically.

Prisms

A prism takes a polygon and stretches it into the third dimension. A triangular prism, pentagonal prism, or octagonal prism follows this pattern.

Antiprisms

Antiprisms twist the top and bottom polygons relative to each other, creating a zig-zag pattern of triangular faces.

Johnson Solids

These are 92 unique polyhedra with regular polygon faces but no requirement for uniformity or high symmetry. They fill the space between order and irregularity with remarkable diversity.

Duality in Polyhedra

One of the deepest concepts in polyhedral geometry is duality.

Every polyhedron has a “dual” formed by swapping faces and vertices:

The cube and octahedron are duals. The dodecahedron and icosahedron are duals. The tetrahedron is self-dual.

Duality reveals how geometry mirrors itself and exposes the hidden balance within shapes.

Polyhedra in the Real World

Polyhedra are not just mathematical art—they appear everywhere:

Crystals naturally form polyhedral structures due to atomic arrangement. Architecture uses polyhedral frameworks for domes, towers, and tensile structures. Computer graphics rely on polyhedral meshes to model 3D environments. Chemistry and biology use polyhedra to describe viral capsids, carbon molecules, and bonding patterns.

Across disciplines, polyhedra function as both practical tools and conceptual bridges.

The Enduring Appeal

Why do polyhedra fascinate mathematicians, designers, and scientists?

Because they lie at the intersection of symmetry, structure, and imagination.

A polyhedron is a piece of logic made visible—an abstract rule set crystallized into form. It shows how space can be partitioned, how surfaces can connect, and how order can emerge from simple constraints. Whether viewed as art, mathematics, or engineering, polyhedra remain timeless objects of study and inspiration.